Seo agus Siud Edition 7 June 2019

Marie-

This is an account of the long and colourful life of Thérésia de Cabarrus known as Madame Tallien and Princesse de Chimay. It is based on various online sources, biographies and Mairin Barrett’s book, Mère Thérèse. So as not to spoil the flow of the narrative, I will not differentiate between my sources or make any attributions. Barbara McArdle

.

Thérésia de Cabarrus was one of the most controversial women in French history. Famed for her beauty, marriages, liaisons and her interventions on behalf of supplicants during the Reign of Terror, she was described as the queen of high society. She lived through the momentous events of the French Revolution and interacted with most of the high profile figures of the day. Many biographies and a number of novels have been written about her, one of them by current day Princesse de Chimany. She is referenced in the Scarlet Pimpernel books by Baroness Orczyand and along with Tallien is a character in one of them. Thérésia was the acknowledged beauty of her day, rich, high-

In February 1789, the very year the French Revolution began, and 4 months off her 15th birthday Thérésia was married to the Marquis Devin de Fontenay, a counsellor in the pre-

The young Thérésia was an immediate success in fashionable society. Her grace and beauty enchanted all who met her. The composer Daniel-

Her father was Comte Francois de Cabarrus, a rich banker and businessman who had settled in Spain, her mother was Spanish. Thérésia was born in near Madrid in 1773, when Madeleine Louise Humann, born in Strasbourg in 1766, would have been 7 years old. Thérésia was educated in Paris in the last years before the Revolution. Her education, typical of the time with its emphasis on the arts rather than scholarship, left her accomplished in the arts of conversation, watercolour and music (piano, harp, guitar, and voice), which she loved with a passion.

However as the years went by the high revolutionary ideals of liberty fraternity and equality were developing into just their opposites. The order of day was now imprisonment and intolerance of difference leading to the guillotining of aristocrats and those who disagreed with the current faction in power. The climate of the time was now one of fear. The Reign of Terror had begun. The heady excitement of the early years of the Revolution was gone. The storming of the Tuilleries in August 1792 leading to the imprisonment of the royal family and finally the execution of King Louis XVI in January 1793 must have been a catalyst for the de Fontenays and others of their class to fear for their lives. If the King could be executed and the Queen and the royal children imprisoned, who could be safe?

The Fall of the Bastille occurred several months into her marriage and she tells the story how shortly afterwards, she was given a tour of that notorious prison. Thérésia, though still a teenager to our eyes was nevertheless equipped by upbringing and education to hold her own in the salons of the day. She had her own salon now and it and those she frequented were buzzing with political discussions, ideas of reform and gossip about the momentous events taking place around them. She would have been a witness to the ever changing loyalties and political theories of the developing French Revolution and also the fluctuating fortunes of the aristocrats and major figures of the time.

Early in February 1794 Tallien was recalled to Paris by Robespierre who accused him of loose living and a lack of enthusiasm for the Revolution. Thérésia followed him to Paris after a few months. Things were going from bad to worse in France: Christianity was abolished by law and most of the churches were closed. Notre-

Tallien, a former journalist was a rising star in the ever changing politics of the Revolutionary government. He had been sent to stir up the revolution in the area, which he proceeded to do with a great show of enthusiasm. Thérésia by now had set up her own establishment in a large apartment in the Cours de Verdun and Tallien who already knew her slightly from Paris was among the many visitors. When Thérésia was arrested and imprisoned that December, Tallien, already captive to her charm and beauty, was able to have her released thus saving her from the guillotine. Shortly afterwards, they became associated together and Thérésia became his mistress. Her relationship with Tallien put her into a position of power and she made good use of it. She was tireless in her efforts to save prisoners from execution, getting false passports for people on the run and seeing them to safety. She used her influence over Tallien to snatch prey from the guillotine and he complied, despite his dislike for Royalists and the risks to which he was exposing himself. Friend or enemy or stranger, it did not seem to matter to Thérésia: their plight as hunted creatures was what mattered. The grateful citizens of Bordeaux used to cheer her in the street, as Notre Dame de Bon Secours.

Madame de la Tour du Pin who owed her life, and the life of her family to Thérésia, has given a detailed account in her Memoirs of how they were rescued. Thérésia went to the greatest trouble and risk to get passports for them, then she procured passages on an American ship, and with tears of joy on her face she saw them aboard. Madame de La Tour du Pin also relates that among others whom Thérésia helped to escape was her former husband, the Marquis de Fontenay, whom she had little reason to love. Though he had been released by Tallien, he was in danger so long as he remained in Bordeaux but at this point he was penniless. Madame de La Tour du Pin tells how he appeared at Thérésia’s house, in wordless supplication; she herself saw Thérésia empty her jewel case of all its contents, tie them up in a handkerchief and hand them to de Fontenay, saying ‘Take them all.’ He took them and left without a word. ‘Take them all’, that was typical of Thérésia. With her there were no half-

During these same weeks of the Great Terror, Tallien and his colleagues in the legislature, were becoming nervous of how Robespierre kept looking towards them in the chamber. They began to fear that they would be in the next purge. The impetus for Tallien and his faction to take action against the powerful Robespierre was a note wrapped in a dagger that Thérésia managed to get to him on 26 July. She tells him that she is now on the death list and accuses him of weakness for not attempting to free her. “I die in despair at having belonged to a coward like you”. Tallien spurred to action brandishes the dagger in the chamber, declaring he would use it if the Convention didn’t have the courage to arrest Robsepierre. The result was the downfall of Robespierre. He was charged with “tyranny” and “dictatorship”, and within twenty-

Robespierre who detested Thérésia had her seized and thrown in prison. Initially, she was kept in solitary confinement in a windowless cell. After 25 days her conditions improved and she was allowed associate with the other women prisoners. Here she came to know the widowed Rose de Beauharnais, the future wife of Napoleon who was to make her change her name to Josephine. This was the time of what became known as the “Great Terror”. An orgy of killing broke out: over the months of June and July in 1794, 1,400 unfortunates were guillotined. Thérésia and Josephine had good reason to fear for their lives: every morning brought the officials with their dreaded list of the those were to be tried that day. Since the ‘trial’ was merely an identity check, there was no hope of escape from the guillotine.

After the passing of a new law in 1792 legalising divorce, Thérésia and de Fontenay applied to have their marriage dissolved. When the decree was obtained in April 1793, they fled south meaning to part company in Bordeaux, Thérésia was to seek refuge with her uncle and brother there and de Fontenay was to journey on to Martinique.

Thérésia went back to Bordeaux briefly to settle affairs and retrieve her young son, Théodore, and several months later in December 1794, she and Tallien were married in a civil ceremony. Having learned from experience, she had a rigorous marriage contract drawn up which left her in complete control of her assets. Shortly afterwards, she gave birth to a daughter christened Rose Thermidor Tallien, called after Josephine de Beauharnais who became the child’s godmother. Some time after their wedding they moved into a residence that had been part of Thérésia’s dowry. "La Chaumière", as it was called, became famous as housing arguably the leading salon in Paris. She had it painted to look like a stage farm, with carefully imitated dilapidated bricks and woodwork and a roof of moss-

With the lifting of shadow of the Terror, Paris went mad: the fear and grief that had robbed Thérésia and her generation of their youth had to find an outlet. A mania for dancing swept Paris, hysterical gaiety and licentious behaviour became the norm for people who had lived too long on the edge of terror. Thérésia became the leader of fashionable society. She went out every night scantily dressed in muslin gowns, but covered in diamonds, rubies, sapphires and other precious stones, and wearing pink and gold wings on her head. Just as today where crowds gather to view celebrities so they waited outside theatres just to see the still only 21 year old Thérésia. A number of years later when she appeared at the Louvre accompanied by her children, so many spectators flocked to see her up close, that she had to escape down a staircase to save herself.

She and Josephine went everywhere together. They paraded down the Champs-

The execution of Robespierre on 28 July 1794 marked the end of the Reign of Terror. Tallien rushed to the Carmelites prison and had Thérésia released. It was characteristic of her that one of the first things she did was to visit Josephine's two children to tell them their mother would soon be free. When the story of Thérésia’s involvement in Robespierre’s downfall became known the 21-

By 1795 Thérésia’s marriage, which had been one of convenience on her side, was failing. Her sense of justice and concern for others made it difficult to love or admire a man who had committed so many acts of cruelty and after the Battle of Quiberon where Tallien had 950 Royalists soldiers who were still prisoners shot in 1795. she didn't want to have anything more to do with him. "He has too much blood on his hands", she said. They separated but didn’t divorce.

Clémence seems to have been especially close to Edouard. She was to live with him in later years as a young adult before her marriage. Edouard studied medicine and became a distinguished physician whose clientele included Alexandre Dumas, Balzac, Victor Hugo, Charles Gounod, and Emperor Napoleon III. He was nick-

1804 the year of Napoleon’s coronation as emperor brought more changes to the now thirty-

A huge crowd from around the region attended her funeral. Few persons have lived lives so representative of their times. "What a novel my life has been!" she declared in old age. The decades of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire remain some of the most event-

Her daughter La Baronne de Vaux, would have been 35 at when her mother died. Her husband Francois-

The autumn of 1795 saw an intertwining of the lives of Thérésia, Napoleon Bonaparte, Josephine de Beauharnais and Paul Barras, then one of the five Directeurs who now controlled the executive of the French Republic. One day, Barras, reputedly the most powerful man in France and a frequent visitor to La Chaumière brought with him the young brigadier general Napoleon. He was painfully thin and so shabbily dressed that Thérésia took pity on him and had a new uniform made for him. History has it that they had a brief flirtation and that she refused his offer of marriage. This partially accounts, perhaps, for his later hostility. Napoleon soon becomes enamoured instead of Josephine Beauharnais. Josephine at the time was Barras’ mistress, but was soon persuaded to accept Napoleon’s advances as this was in Barras’ interest also. She and Napoleon married quietly in a civil ceremony in rue d’Antin in March 1796. Barras and Tallien were in attendance. For those who like connections, this was also the day where in the same area of Paris, that Louis Bautain was born in rue Beaubourg

Thérésia now became associated with Barras with the result that Barras, one of the most powerful man in France now had the most beautiful woman in France for a mistress and as hostess for his endless receptions, balls, and entertainments at "La Chaumière," the Luxembourg Palace (where the Directors resided), and his Château de Grosbois, which had once belonged to Louis XVI's brother, the future Louis XVIII.

Along with her strictly social role, Thérésia continued to answer pleas for help or favours. Most of her non-

There, in the rue de Babylone on February 1, 1800, Clémence, the future Mère Thérèse de la Croix was born, and christened Clémence Isaure Thérésa Tallien. Are there parallels to be drawn between Thérésia’s choice of Clémence as a name and the clemency she so frequently sought on behalf of others? Clémence Isaure is a semi-

1799 saw the downlfall of the 5 man Directory and start of Napoleon’s reign as Consul. Thérésia and Barras parted by mutual accord, but remained on friendly terms. Thérésia began a liaison with the millionaire banker Gabriel-

Life was not plain sailing for the amorous couple. His family, of old nobility, strongly disapproved and the prospective match because of Thérésia’s reputation, and there was the matter of Thérésia’s original husband, de Fontenay. for there was no question of anything but marriage. Her civil divorce from de Fontenay, her marriage to Tallien and its subsequent divorce didn’t count in the eyes of the Church or the de Riquest-

The couple were married in August 1805 in a quiet ceremony at Saint-

Francois-

Her charitable work helped her overcome the depression she suffered because of her exclusion from court functions at The Hague and in France. Her past liaisons and revolutionary past were an obstacle to her acceptance at the courts of either Napoleon or the restored monarchies of Louis XVIII, Charles X and Louis-

Thérésia had four children with Francois-

At Chimay, Thérésia became a much-

She did not receive the support from her husband she might have expected and feared he would see her as an obstacle to his advancement. She wrote that she felt useless and wanted to die and asked him in a letter to tell her that he didn’t regret having married her. In the end, she refused to be broken by her exclusion and by the calumnies to which she was becoming exposed in recently published memoirs: "I have lived to this day," she wrote to her son Edouard on July 25, 1829, "without having caused any tears to be shed, without having experienced a feeling of hatred or desire to take revenge; I want to die as I have lived."

For years she had suffered from liver disease. Eleven childbirths, a dangerous proceeding in those times, also took a toll. She visited spas at Plombières and Dieppe; while at Nice in October 1830 she experienced a crisis which recurred in July 1834, and she declined thereafter. On January 15, 1835, she had herself carried to the terrace outside her room to savour the view one last time. That night at about 10 p.m, she died aged 62

Both lived through the tumultuous years of the French Revolution. Both were women of influence and engaged with the events of the Revolution according to their convictions: Louise worked to combat the effects of the persecution of the faith in that godless time. Thérésia was indifferent to the faith she was born into during those years, but nevertheless was engaged in “good works”. They were women of vastly different interests but with a similar inclination to be of service. Louise sought to save peoples’ souls, Thérésia sought to save their lives. Louise was the spiritual mother of Louis Bautain, Thérésia was the actual mother of Mère Thérèse. The influence they brought on these, our two ancestors, is what links them. Barbara McArdle

And to make more connections:

Thérésia and Madeleine Louise Humann were contemporaries but very different women.

Thérésia’s children would have been looked after in a “pouponnière”. Pouponnières were select nurseries which received even tiny infants a few days old, and boarded and cared for them until they were five or six years old. Clémence and her brother and sisters were happy in their nursery which was run by a married couple called Choisel. They had a large garden to play in and the Choisels were fond of their charges. The Choisel nursery was in Boulevard des Invalides, only a street or so away from their mother's house; every so often she would call or send the carriage to fetch them. They would be shown off and fussed over and then sent back to Papa Choisel. Until Clémence was six or thereabouts, her real home was with the Choisels.

Maximilian Robespierre

Mme de la Tour du Pin

Louis XVI

Marie Antoinette

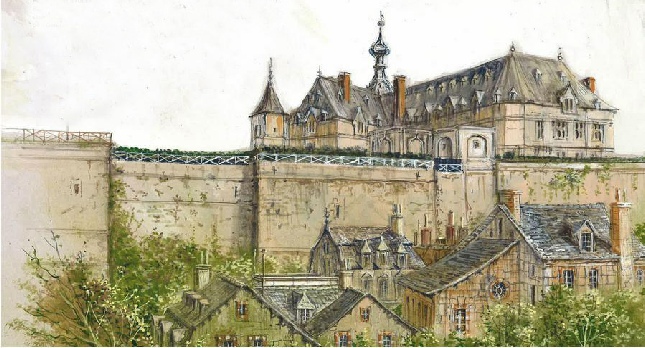

The Storming of Tuilleries Palace

The Fall of the Bastille Prison

St Eustache Church

Thérésia de Cabarrus

The Storming of Tuilleries Palace

Bordeaux was relatively calm after the turmoil of Paris where the executions continued daily. After a show trial in August and 2 months of solitary confinement, Marie Antoinette followed the king to the guillotine that October. That same month of October 1793 Jean-

Jean-

Thérésia’s high spirits sat side by side with a kindness and compassion which made her ready to help all who came to her for assistance. She continued to make use of her influence over Tallien and worked to procure freedom for prisoners and to obtain better conditions for the huge numbers who still remained imprisoned. One day her daughter, the Baronne de Vaux, would be engaged in a similar task. She answered a seemingly endless litany of pleas, especially from returned émigrés and ex-

I finish with a paragraph from Mairin Barrett’s book about Mère Thérèse:

People may disagree about many things concerning Thérésia but no one denies her vitality. Her daughter Clémence inherited this vitality which was a marked feature of her life both before and after she became a Dame de Saint-