Seo agus Siud Edition 12 November 2021

Page 2

The small seaside town of Bundoran is where the first branch house of the St Louis institute in Ireland was established. This is an account of some of what we know of that first foundation (1870-

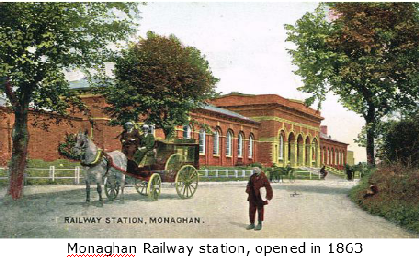

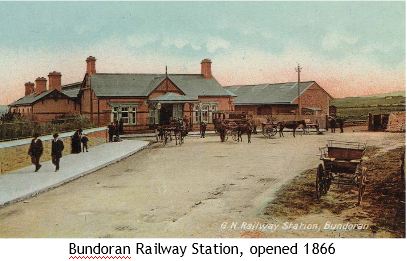

One could say that for the growing St Louis Institute, its early foundations were linked to the expanding railway network in 19th century Ireland. 1863 saw the arrival of the railway to Monaghan, enabling easy access for the young St Louis community to Dublin, a far cry from the journey of the first 3 sisters by Bianconi coaches four years previously. Then in 1866 a branch line was opened to Bundoran further extending journeying possibilities.

The annals tell us that the sisters made regular visits to Bundoran for rest and recuperation and would have been very aware of the poverty visible all round them. Bundoran at that time was still recovering from the ravages of the famine, and despite the growing prosperity its popularity as a holiday destination was bringing to the town, we are told in “God Wills It” that the “effects of dire poverty appeared on all sides. Many of the farmers were not physically fit to till the barren soil; fishermen whose boats had been lost or injured were too poor to replace them.”

Bundoran was already gaining popularity as seaside holiday destination for the middle classes of the time even before the advent of the railway. The small town was expanding rapidly with newly built hotels and lodging houses interspersed with the humbler dwellings of the locals. Those locals, who had space, offered rooms to the less well off visitors. Holiday makers could now travel by train all the way from Dublin or Belfast to Bundoran. So the annals 1867 relate that Mother Genevieve spent a number of months in Bundoran convalescing after an illness. She stayed at an establishment called Tranquila Lodge on the Sligo Road on the outskirts of the town. That building exists today and is a private residence. Genevieve was at Tranquila Lodge, when news reached her of Abbé Bautain’s death on October 15th of that year.

Finally a premises was identified but since it belonged to the above mentioned Connolly Estates and the leasehold stipulated that nobody should let, sell or lease the property “for any popish purposes” it had to be acquired by a third party. The building was a former hotel in the West End overlooking the sea and then known as the Connolly Arms. After the sisters left in 1884 it reverted to its original purpose re-

The Rev Francis Keleghan was an important figure in the history of Bundoran parish and became so in the life of the sisters. He had been a staunch defender of his people during the famine years; and oversaw the construction the current parish church, Star of the Sea, some 10 years before the sisters started to visit Bundoran. But the big talking point from the time the sisters first came to know Bundoran and Fr Keleghan must have been the Right of Way Controversy and his involvement in it.

In 1868 a local landowner, James Hamilton, who had recently purchased land from the Connolly Estates, began building a wall to close off access from the main street to the beach. The Connolly Estates along a number of other landed estates in Ireland were then held by Dublin’s Trinity College for whom the leases and ground rents were a source of income. James Hamilton’s intention was to charge an entrance fee for access to the beach. There was immediate outcry not only from the visitors but more importantly from the local people who used the sand and seaweed for their crops as well as recreating there with “dancing and bonfires”. The protest was led by the redoubtable Fr Keleghan. The ensuing legal action and court case lasted several years and was only finally concluded in 1870 with victory for the local people who were awarded in perpetuity the “public rights of way for horses, carts, carriages, and foot passengers, at all times, from the Main Street of Bundoran to the shore and back again”. The sisters search for accommodation would have taken place against the background of speculation and anxiety as to the outcome of the court case.

Back to 1871 where Marion McGreal takes up the story of the early convent

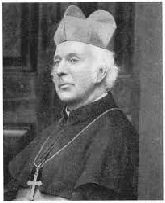

Over the following three years Genevieve must have become convinced that sisters from her growing community in Monaghan could make a difference to the small town of Bundoran. The decision to open another house, some ten years after their arrival in Monaghan, house must have been a major one for the Genevieve and her council. Negotiations commenced between the then bishop of Clogher, Dr Donnelly and Fr Francis Keleghan the parish priest of Bundoran. Genvieve and three other sisters spent 3 months at Tranquila Lodge in 1870 as they searched for suitable premises for a convent.

The new premises needed refurbishment and adaptation for the needs of the new community. We have the written instruction from Genevieve to “examine and repair the seawall. Build a wall across the yard with a large wooden gate framed in iron -

When the premises were ready a boarding school was opened. Fees were £25 per annum. In addition to the basic subjects French was taught, which is not surprising considering that the sisters were trained in France. Visitation of the sick and poor, care of parish church altars and training the church choir were also ministries in which the Sisters engaged.

A National School was opened in which there were 120 children on roll. In 1880 ninety-

Sr. Clare’s account brings some heart warming news at times as in this entry, ‘Mr. Kelly gave us a nice red cow. We called her Fintona and her calf Flake.’ Wouldn’t we all love to know now who Mr. Kelly was. In the community Sr. Martha provided the meals. It would appear that there was never a surplus of food. Sr. Clare writes, ‘Sr. Martha made 4 dinners out of one quarter pound of lamb. She will send the recipe on request. Please enclose stamps’. Sr. Clare could bring humour to a situation which undoubtedly helped in those stringent times.

Existence was a struggle and financial assistance from the Mother-

Mass was offered daily in the convent except when there was a funeral in the parish. The Sisters were happy as they entered wholeheartedly into their various works. Then on November 21st 1881 a fierce storm swept across Bundoran leaving destruction in its wake. The rear of the convent and the wall separating it from the sea were both damaged.

Another hardship came their way exactly a year later; the much loved parish priest, Canon Keleghan died suddenly the following week on the 28th of November. He had offered Mass in the convent two days previously. The sisters were devastated by his passing as indeed were all the people, Catholic and Protestant alike. This good man was long remembered by the people of Bundoran but he didn’t fail to remember them either, he bequeathed £500 for the poor children of the parish.

The sisters continued on their ministries for two more years but the economic status of the convent was problematic. Despite valiant efforts on the part of the sisters, their benefactors and the motherhouse in Monaghan to keep the convent viable it wasn’t possible and the decision to withdraw from Bundoran was taken with great reluctance. So, after fourteen years the sisters made their train journey back to Monaghan.

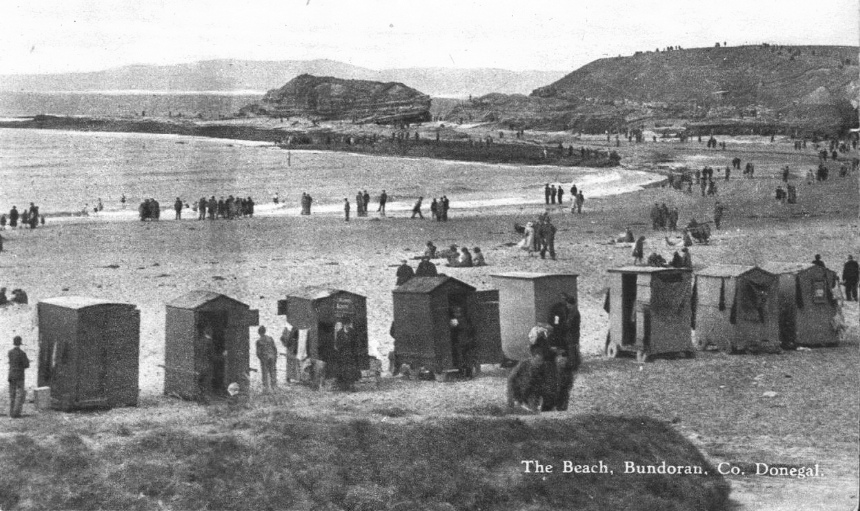

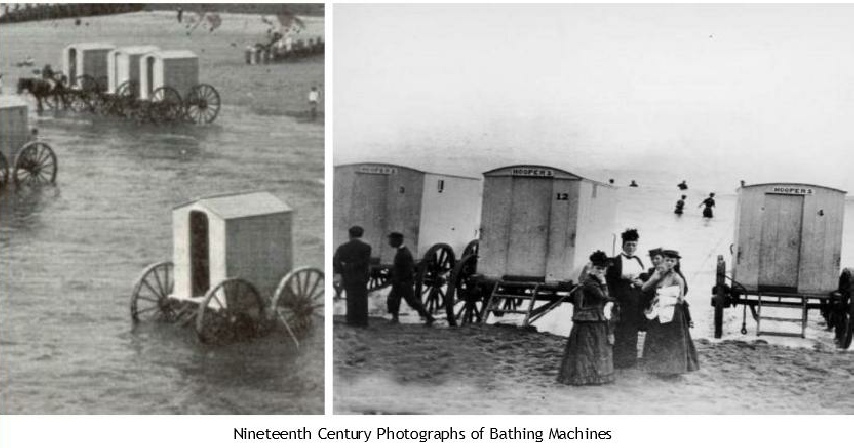

With reference to Genevieve’s request for a bathing house at the foot of the steps from the hotel down to the sea, it might be interesting to think ourselves back into the era of the bathing boxes or bathing machines as they were also called. In those days sea bathing was popular more for health reasons than enjoyment. The bathing box was developed in 1750 by one, Benjamin Beale, a quaker from Margate, perhaps a relative of Genevieve, perhaps not. The idea was to preserve the modesty of those who were squeamish about undressing in public. The bather entered the box at one end, changed into a bathing costume, which was often provided by the bathing attendant. The box was then hauled down to the sea where the occupant could exit from the other end of the box straight into the water. The process was carried out in reverse when the bather was finished.

Continuing with the topic of sea-

There is reference in the community annals to visits from the sisters and boarders:

“Two sisters and 6 boarders coming on holidays” (1878 annals)

“13 boarders with Sr Elizabeth O’Donnovan and Sr Gertrude Tunney have

come on holidays. The boarders are in Miss McGeogh’s lodge.” (1881 annals)

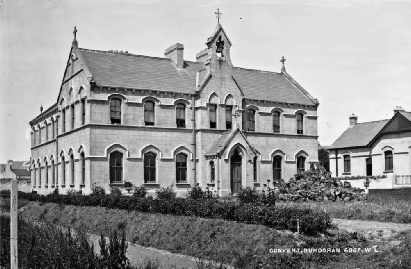

Not everyone will remember or perhaps even know that Bundoran was founded twice. The first foundation was in 1870 and lasted fourteen years, the second was in 1892 when the convent that most of us would associate with Bundoran was built.

Claire O’Sullivan’s diary has a whimsical reference to the work being carried out. “I know nothing of architecture but prudence would suggest not to remove the roof of an inhabited house without having some notion when it is to go back on again”. This entry was in January a month after they moved in. Was she referring to the roof of the main building or to a wing attached. One can only image the hardship of living in a partially repaired building at the sea’s edge in the middle of winter exposed to the gales of stormy Bundoran. Obviously the difficulties of workmen lacking needed supplies and not turning up when expected was as familiar then as it is today.

In the postcard below of bathing boxes in Bundoran, one can see some with wheels, others with what looks like rickshaw handles and others that might have been stationery where the braver bathers would have walked to the sea. Manning the bathing boxes would have given employment to the local people.

Dr James Donnelly

Bishop of Clogher

1865 -

Gabriel in Link gives us a further insight in the difficulties of that early foundation. She writes:

The year 1878 brought the greatest blow of all -

In a letter shortly before Genevieve’s death Bishop Donnelly writes to the sisters in Bundoran “I feel deeply for the smallness of your income amidst so much misery.” Finally in 1884 Mother Xavier Finnegan, Genevieve’s successor, made the decision with the Bishop to close the house and widthdraw the sisters.

In those 14 years they had given themselves totally to this poor area. They has set up a solid national school, a very small boarding school, had visited the poor and sick all over the area, and they had built up the Sunday school. All this in the face of dire poverty, frequent crop failure, and a huge amount of anti-

A map of Bundoran showing places mentioned.

Below are what images we could find of the building, as the Imperial Hotel

The Imperial Hotel before it was demolished in 2007

And so on the 8 December 1870 the first St Louis Branch house in Ireland was opened and blessed by Fr Keleghan. Gabriel tells us in Link:

Genevieve sent her dear friend and co-

The annals give us a further description:

“On the left of the hall there is a parlour and a second room with arching buttresses…these are now the chapel. On the right there are 2 large pantries. One has become a refectory or dining room and the other a bedroom for the children who work in the kitchen. On the first floor are five rooms with arches opening into each other, forming a ballroom. These are now our oratory, a classroom, a music room, a lumber room and a linen room. On the second floor are our community room and four bedrooms. At the other end five rooms have been broken into a dormitory for the boarders. Kitchens and sculleries are in the wing-

An aerial view in the 1950’s